I’m pleased to announce the publication of our study on the coordinate frames of spatial hearing in this week’s issue of The Journal of Neuroscience. The paper was posted on BioRxiv a few months ago and has now been peer-reviewed for J. Neurosci. The full paper is available here, but this blog post outlines the main take-home points from the study…

What’s the study about?

My research is interested in understanding how listeners infer the location of sounds in auditory scenes. For us as humans, we often think of sounds as being located in specific spaces; for example, when your alarm clock rings, you can say “the clock is by my bed” or “the clock is on my left”. These two descriptions reflect different coordinate frames in which space is defined - either by objects in the world (sometimes called allocentric space) or by the observer (sometimes called egocentric space).

The core distinction between these spaces is that world-centered space is stable when we move; the alarm clock is still beside the bed after you’ve got up to brush your teeth, but (because you’ve moved) the position of the clock has changed relative to you. We know that humans can easily access information about sound location in both these spaces, but now we show the same ability in animals (ferrets).

How can you show how animals think?

Obviously animals can’t talk directly to us and describe their experience. One way around this is to design tasks that have unique solutions; if the animal can solve the task, it must be able to access information underlying the solution.

The details are in the paper, but briefly we designed a task that could only be solved by localizing sounds in the world; it works by presenting ferrets with sounds from one of two locations (East or West) and asking them to report which location was presented at two response ports in the North or South of a test arena. Animals do this when the test sounds are presented from many different directions, which makes the head-centered position of sounds uninformative about the correct response. The fact that ferrets could learn to do this indicates that they could use the world-centered position of sounds to guide behavior.

We also designed a complimentary task in which animals had to use head-cented information to discriminate sounds from in front / behind the head across changes in sound location in the world. Ferrets also solved this task as well, indicating that like humans, they can think about sounds in multiple coordinate systems.

How do you know the ferrets aren’t cheating?

This is an important part of any behavioral study, where we model the possible solutions to the task, and then compare models to animal behavior. In our study, we tried a variety of different systems to see if any solved the world-centered task without using world-centered location. We did identify a few models that could perform well under certain conditions, but these models failed when we looked at the responses of ferrets on probe sounds.

Probe sounds were presented from untrained locations (e.g. the North-West or South-East) and so gave us an opportunity to see what animals thought about sound space in general. Ferrets treated these sounds as if they existed as part of a continuous space (i.e. if the sound is half-way between two trained locations, respond equally often at the two response locations). Only a world-centered model could account for this behavior.

Is it just ferrets that can do this?

Our work was the first to show non-human localization of sounds in multiple continuous spaces, but there are hints that other animals can do this. Work in gerbils for example shows that they can detect changes in world-centered sound location. Likewise, anecdotal evidence suggests that cats can form expectations about their owner’s voice location that are fixed in the world. That makes sense because cats have highly mobile ears (pinna) that dramatically change the properties of sounds arriving at each ear. It would thus make sense for them to represent sounds in a world-centered space that remains stable across changes in ear and head position. The same is probably true for most mammals, and probably birds as well.

Why is it important to study animal cognition?

There are two reasons related to biomedical and technological developments.

Firstly, animals provide a vital window into how brain function underlies behavior in ways that simply aren’t possible to study in humans. For instance, our earlier work has studied how neurons in the auditory cortex represent sounds in different spaces and used reversible inactivation to switch this brain area off during behavioral tasks. Neither of these studies is possible at present in humans, but reveals fundamental new knowledge about physiology that helps us understand how the brains of humans work, and how that might break down - for instance in auditory hallucinations, where the externalization of sound sources is problematic.

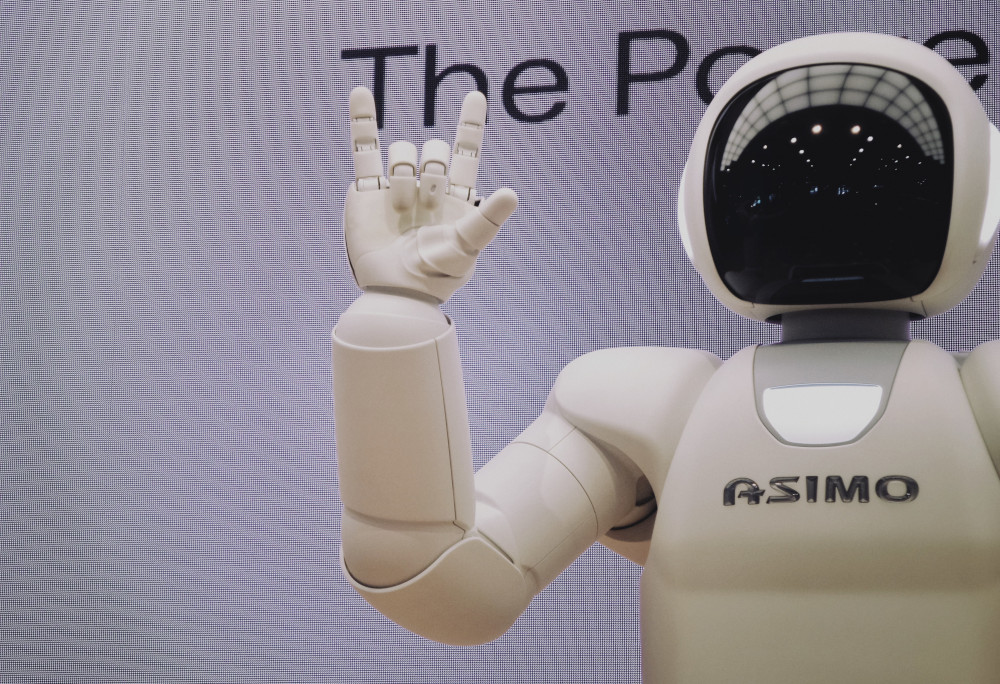

Secondly, the development of intelligent machines can be accelerated by understanding the behavior of animals. Animals have obviously survived on this planet for hundreds of millions of years, and show a general level of intelligence that may be desired in artifical agents. World-centered spatial hearing is an intruiging example of how listeners combine incoming sounds with internal models about themselves and the world in order to map auditory scenes. These abilities parallel the developments in simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) techniques in robotics using methods such as LIDAR. Understanding how animals deploy world-centered models in natural behavior may thus be helpful in creating biomimetic systems that can persist in environments without external guidance.